Many of our clients include Nomadic’s programmes in their own internal training catalogues, and the training department then makes a respectable effort to promote these programmes. As a supplier, of course we appreciate that because its what gives us business. But, does it make business sense for our clients too?

Within the field of L&D, the discussion on whether or not to publish a training portfolio to staff is one that has been ongoing for decades.

As a management trainer at KLM Royal Dutch airlines, I was already part of that discussion in the 1980-ies. As a corporate training department, we ran our unit like a small business, creating attractive programmes such as presentation skills, negotiation, time management and finance for non-financials.

We did our best to market these training programmes and fill the groups. At the same time there were business units that decided to radically move away from internal training departments and catalogues. Their idea was that developing employees is the responsibility of the manager and that a catalogue of training gets in the way of that process.

Indeed, managers often use the training catalogue at appraisal time, to see what course (s)he can offer to the employee the coming year. The downside of this is that there are participants who are ‘sent’ to training because their boss felt the person needs to be ‘fixed’.

The manager delegates employee development to the training department and does not do her own share. This scenario is doomed to fail: an employee does not radically change behaviour over the course of a 3-day communication training and after returning to work it’s often ‘back to normal’.

Another unintended use of catalogue type training is offering training as a reward for good performance. This type of training participant is not necessarily the most engaged one in the learning process.

I remember an operations manager from a former Eastern bloc country coming to the Netherlands for management training. When I asked how he enjoyed it, he replied, with a heavy accent: ‘I like management training; nice breakfast, nice lunch, nice dinner!’

So, which positioning approach to training is best? And what makes sense from a didactics standpoint?

Ideally, the manager identifies a development need (NOT a training need) in a dialogue with the employee.

For instance, they may establish that an employee needs to develop project management skills, because she will play a key role in the coming year coordinating an important project.

Next, they discuss which way these skills can be best developed.

Many organisations use the famous 70/20/10 rule. This originates from the ‘Lessons of experience’ ongoing research project by the Center for Creative Leadership that started in the 1990-ies. The question at the heart of this research is what constitutes a significant learning experience in the development of leaders.

The graph below shows that experience (including hardship) is the most important source of learning, supported by other people. Training (as well as reading), although only 10%, is not unimportant but can have an amplifying effect on the learning from experience.

in the case of the employee needs to develop her project management skills, the task of the boss is to identify the right, on-the-job experiences that develop these skills, supported by people and possibly formal training. The boss her/himself is one of the ‘other people’ and has a key role in making the learning happen and stick.

Another key element in designing training in the workplace is the ‘transfer of learning’: what happens after the employee has attended training.

Is it ‘back to normal’ or is there a plan to actively encourage employees to implement and integrate what they have learnt. In our example: is the team member who attended project management training given the space to use the new skills and make changes to the current project management practices?

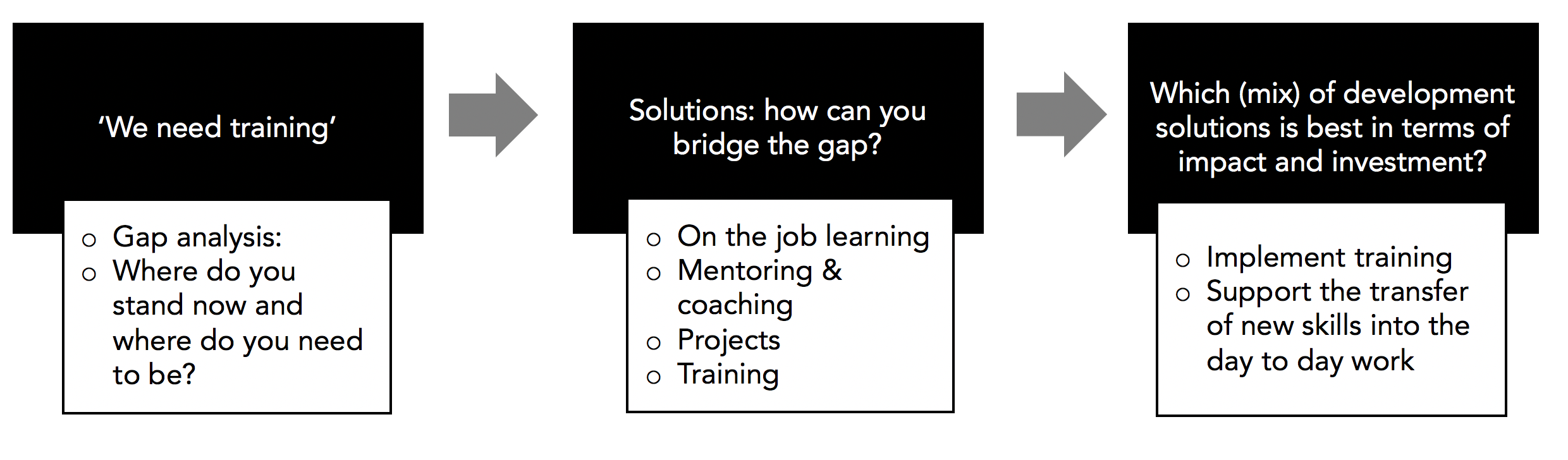

Graph: Learning Needs assessment in 3 steps:

Questions to ask to identify learning needs

When a client asks us to provide a training programme, we always do a ‘learning needs analysis’ to know in detail what the problem is before we start designing the solution. It’s about identifying the gap between current and future performance in a specific domain.

To this end, we ask questions like the ones below, either in a survey or an interview.

- Why is this development important for the organisation?

- What are the goals for this team /audience in the short / medium/ long term

- What are the job descriptions and how might these change in the future?

- Why now?

- What is going well at the moment?

- What needs to be done differently?

- Where is the ‘pain’ in the team / unit / organisation?

- What would happen if you didn’t provide this development to these employees?

- Who is the driver of this initiative? What is her/his interest to invest in this development?

- What would success look like?

- What other ways are there in the day to day work to learn these new skills?

- How is the application of new skills supported in the work environment?

- How do employees feel about investing their time & energy in developing these skills? Are they motivated?

In summary, training programmes in organisations make a valuable contribution, as one piece of the development puzzle. Other pieces of this puzzle are: a thorough needs assessment, development minded managers and creative thinking of how the workplace itself can be used as a vehicle for learning & development.

See here how Nomadic IBP’s virtual classroom expertise can support your L&D efforts.

We are always happy to answer your questions about training needs and to share our expertise on how to provide the most effective programmes for your team. You can also visit and use our resources page to learn more.

Image source: www.freepik.com

Fredrik Fogelberg is a chartered Organisational Psychologist specializing in leadership development and team facilitation in international organizations. He has over 30 years of international experience in the corporate world and as a consultant.